Intellectual Authority

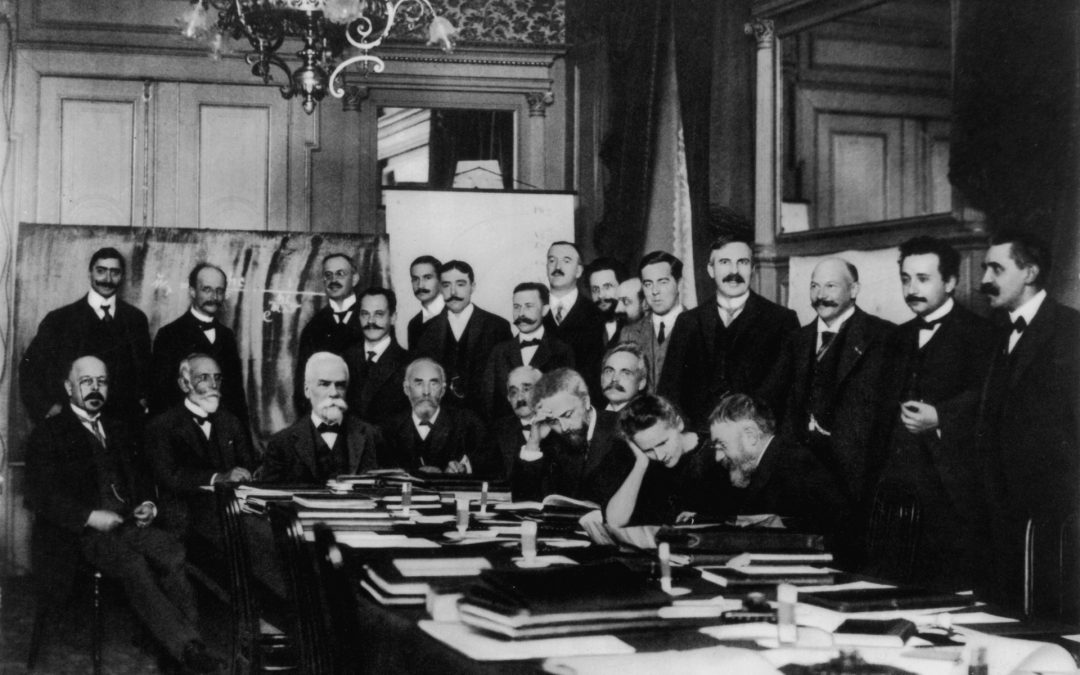

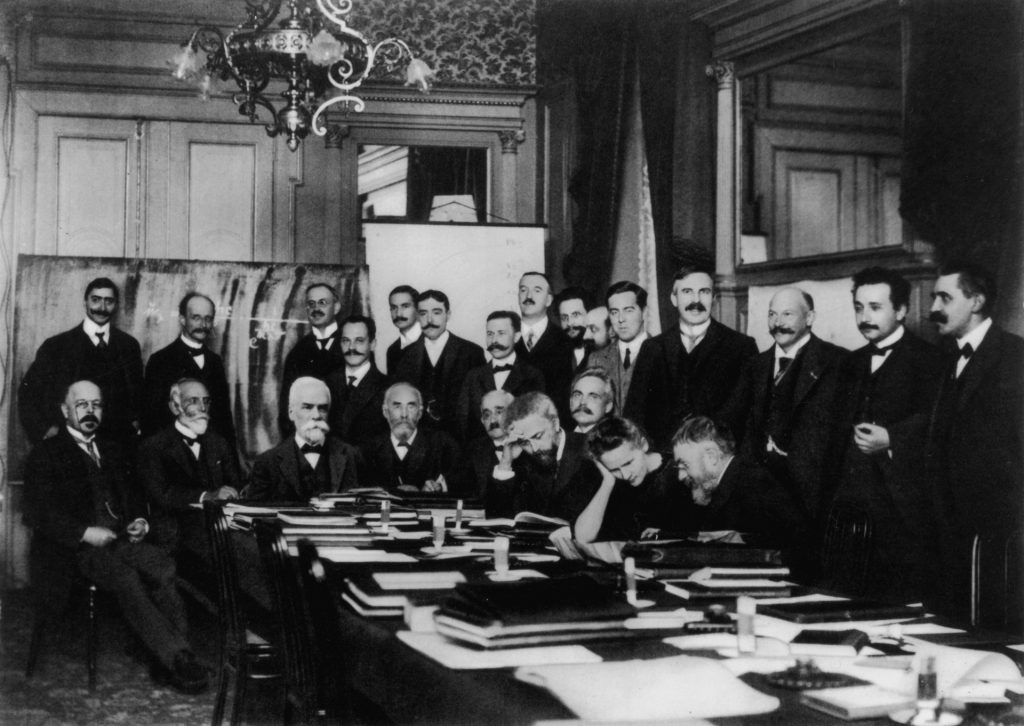

Photograph: the first Solvay Conference in 1911, including Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, and Max Planck.

This is the second essay in my series on intellectual legitimacy. Read the first essay here.

It is always a pleasure to have an excuse to mention underrated thinkers. Robin Hanson is one of my favorites, with dozens of original ideas to his name. His career as a communicator spans everything from coining the term Great Filter in cosmology to writing a book on the inner workings of the human brain. While working as a physicist at NASA, Professor Hanson had the idea now known as futarchy: a system of government in which some of the decision-making power is held by prediction markets.

Physicists, however, do not have intellectual authority on the topic of how society should be run. Economists do. The intellectual legitimacy of an idea partially depends on whether it is proposed by someone with intellectual authority. Intellectual authority is a personal reputation. It reflects not only perceived expertise, but perceived pro-social orientation of the individual. Intellectual authority rests with people who are seen as possessing good intellectual judgement that is not only technically correct, but also takes into account social and political factors. Compare, for example, the perceptions of Garry Kasparov and Bobby Fischer. Both legendary chess grandmasters, but the former a celebrated public intellectual, the latter considered a tragic cautionary tale due to his erratic, offensive, and sometimes illegal behavior. Such perceptions are of course also contingent on institutional endorsements and can be changed by them.

As reported in Fortune, Robin Hanson “says he went to the expense and trouble of getting a Ph.D. almost entirely so that people would take him seriously … he was thinking up market-based improvements to government institutions, but found that with his techie background he couldn’t get anyone … to listen. So he went to CalTech to get a Ph.D.” Now branded as an economist, Hanson was soon implementing a pilot prediction market for the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA). Today, Hanson’s work is often cited by leading commentators and intellectuals such as Nate Silver and Tyler Cowen. By understanding how to acquire the relevant intellectual authority, Hanson gained an audience for his idea he couldn’t have had otherwise. Indeed, it is likely that the productive frontier for his work lies not in new ideas, but in improving his intellectual authority to help advance his many existing ideas.

The intellectual legitimacy of ideas is partially determined by who communicates them. The messenger matters for the reputation of an idea. Often those with the highest intellectual authority aren’t necessarily the most generative. As a consequence, credit for originating a legitimized idea nearly always flows to the person with the highest intellectual authority that has a claim to it. This inspired what is known as Stigler’s law of eponymy which states no scientific discovery is named after its original discoverer. Fortunately, this law doesn’t quite hold. Generativity, validation, and authority can be aligned through functional institutions, although this is an exceptional rather than ordinary state of affairs.

Different social roles hold different amounts of intellectual authority. The academic has more intellectual authority than the journalist, who in turn has more authority than the blogger. The god-king, a now-extinct social role, could claim complete intellectual authority over all domains. A social role need not be extant in a given society to have intellectual authority: Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations wouldn’t be as widely read today if he hadn’t been a Roman Emperor.

Social roles

Figure 1. Authority of different social roles.

The intellectual authority of these different social roles themselves can change over time. In this way such roles are an example of borrowed power: one can use one’s socially legible role to legitimate one’s ideas, but at the end of the day one’s social role is contingent on a broader social landscape that is prone to change. The king, while he may still hold the ability to issue honors, holds much less intellectual sway today than he would have in 1650. The English Civil War, as well as the American, French, and Russian revolutions are significant causes of this shift. The intellectual authority of a role changes with success or failure at social, economic, and political competition between niches.

Figure 2. Authority can shift over time.

Legible intellectual successes can change the authority of a social role as well. A good example of this is 20th century physics. The triumphs of theories such as general relativity and quantum mechanics greatly enhanced the intellectual authority of the profession. The detonation of two atomic bombs in wartime also demonstrated this new mastery of physics as vital to state interests and war. This drove physicists such as Einstein to comment on statesmanship and others like Oppenheimer to even try their hand at it, with mixed success.

Figure 3. The intellectual authority of 1940s physicists. Left: The New York Times reports on the 1919 Eddington experiment. This confirmation of general relativity was remarkably publicly legible – as with the newly-enhanced intellectual authority of physicists. Right: Members of the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, founded 1946.

The fields of study themselves change with new discoveries and developments, as do the people who pursue them. The archaeologist in 1880 has a somewhat wider ability to comment on science and society than does the archaeologist in 2020. The archaeologist of the 1880s is a gentleman who pursues knowledge of the distant past, usually on his own dime, and who can have his wife bejeweled as Helen of Troy when announcing finds. The archaeologist in 2020 is an academic who has to stick to very narrow claims to avoid career death.

One might think professionalization means a strict improvement in the epistemic foundations of a field. This isn’t the case. Rather, professionalization is a way to reduce variance. Professionalization is essentially the creation of set procedures, norms, and social roles to govern a given area of knowledge, and while this eliminates unserious crackpottery, it also crowds out the “unorthodox” and often stochastic experimentation employed by all exceptional live players as they drive new fields forward—in short, reducing variants cuts off both tails of the skills distribution. While professionalization does eliminate some malpractice, for pre-paradigmatic fields it can be harmful, since researchers must pursue hypotheses that can’t be justified to bureaucrats. If the hypothesis could be justified to bureaucrats the field would already be mature. A premature professionalization closes many doors of inquiry.

Archaeologists today are less likely to change their historical views based on new finds than their 19th century counterparts. The latter saw no problem in integrating evidence of previously unknown civilizations, including the Hittites and the Sumerians, when digs suggested it. The long and slow road of evaluating modern finds such as Göbekli Tepe in Turkey serves a notable contrast. An impressive 11,000 year old structure featuring hundreds of pillars, a 50-foot tall artificial mound, and statues and carvings of animals, the find showed neolithic construction to be much older than the previously accepted 8,000 years, as a consequence also predating the consensus origin story of agriculture. The archaeological site was actually first surveyed in 1963 by an effort of the University of Chicago, but they incorrectly identified the distinct T-shaped pillars as a medieval cemetery, matching preconceptions. The German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt stumbled on these records while searching for new dig sites in 1994. He found them unpersuasive. It then took Schmidt nearly two decades of excavation work to overturn the field’s previous orthodoxy.

Figure 4. Change in authority of archaeology.

The social roles held by an individual can themselves shift over an individual’s career, changing their intellectual authority. The well-cited academic was once a PhD candidate, the seasoned security expert was once a novice security engineer, and the practicing surgeon was once a pre-med student. Jumps between careers can make this change in intellectual authority particularly stark. People mocked Arnold Schwarzenegger as a mere actor when he ran for and won the governorship of California, but in a way these remarks showed Schwarzenegger had finally made it. When he was merely the star of a streak of blockbuster movies, people would mock him for not being a real actor. His career had started in bodybuilding, after all.

Figure 5. Authority may change over an individual’s career, especially if they adopt new social roles.

Sources of Personal Intellectual Authority

Are changes in social roles the only source of change to an individual’s intellectual authority? Not quite. All changes in personal authority are ultimately traceable to four sources:

1. Bureaucratically-issued

The simplest example is authority issued by an institution that people trust. These institutions might have a single or several representatives, but have a procedure in place for ascertaining whom to legitimize. This means that such institutions are always somewhat bureaucratic. If one bases their intellectual authority on this source, it is strongly correlated with the authority of the institution itself. Examples include: PhDs from Harvard, economists at the Federal Reserve, rocket scientists at NASA. Were any of these institutions’ reputations to suffer, the individuals would take a hit as well, even if they had no part in relevant failings.

2. Great feats

A great feat by an individual can be the basis of intellectual authority in the domain of that feat. Examples include Buzz Aldrin’s authority to comment on space-related matters, Viktor Frankl and Antarctic voyagers’ authority to comment on overcoming hardship and the human condition, and Bill Gates’ authority to comment on development of the internet and computers. Bill Gates is also a good example of a notable subcategory of such feats, namely producing large amounts of economic value in a domain, which he has parlayed into a recognized ability to comment on energy, public health, and philanthropy.

3. Third-party endorsement

Similar to authority via bureaucratic issuance, one can obtain intellectual authority in a domain through the personal endorsement of someone who themselves has authority over that domain. A book on foreign policy is more authoritative if it boasts an approving blurb from former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. The scope of the authority transfer is limited and tied to the endorser’s existing authority—while a personal endorsement from John Doe will likely cause John Doe’s personal network to believe you, your credibility in the eyes of the general public will be more limited.

4. First-person authority

The final source of authority is personal intellectual authority. One must deliver two components to obtain personal intellectual authority: intellectual material and a marker that you claim and deserve intellectual authority. An example of a pure marker might be prefacing an opinion on social media with “I’ve read several books on this and…”. Another more extreme example would be Buzz Aldrin punching moon conspiracy theorist Bart Sibrel in the face after the latter claimed that Buzz did not land on the moon.

One can also deliver material without signaling that one deserves authority. In this case one does not gain authority. Many fail to do this; it is especially common with those lacking social awareness. At the other extreme are those who use formal and pseudo-technical language as a marker rather than as a means to convey material. The two extremes sometimes happily coexist in ignorance in the same subcultures.

These four categories might be well illustrated by thinking about intellectual authority in physics. If you have a PhD in physics, your words about physics are assumed to be sound. When the physics PhD talks, they’re speaking from the authority of the institution. Contemporary physics is in this case professionalized, much as archaeology is. The professionalization is regulated by social networks and bureaucratic bodies. Most physics PhDs and physics professors are then relying on the physics and academic establishments for their intellectual authority.

A typical physicist is well contrasted with Albert Einstein. He is authoritative on his own and speaks on behalf of his own theories. The legitimacy of his ideas is not granted by an institution. How did he reach this position?

Albert Einstein first performed great feats such as producing special relativity—which examines the relationship between space or time—and explaining the test results of the photoelectric effect. These two examples alone demonstrate Einstein’s intellectual range. The former clarifies theoretical relationships, while the latter develops new theory to explain a surprising experiment.

It is striking that the intellectual legitimacy of the ideas published in his Annus Mirabilis papers ultimately added to the intellectual authority of academia, when before publication academia had frustrated Einstein’s efforts to find a position. His most well-known work was mostly done while he was a patent clerk, working outside of academia. This is a common pattern. The dynamics are similar to Stigler’s Law of eponymy which we considered earlier. Perhaps we could call this pattern “Stigler’s tax”: any discovery that is eventually accepted by academia is ultimately claimed to have originated from academia.

As Benjamin Franklin remarked, of all the things in this world one can only be certain of the inevitability of death and taxes. So, paying our due, what measures can an individual take to harmonize their own production of intellectual material with personal markers of accomplishment? In contemporary society there are two notable ways to gain personal intellectual authority without having to route through normal institutions.

The first one is writing a book. Becoming a public intellectual through publishing a book on a social topic, especially a “pressing issue of our time”, is a good method of building first person authority. The book must contain intellectual material, but is also a marker that you deserve authority. Contrast this with a series of blog posts, where the primary concern might be improving the material or writing to friends.

The second common route is through creating economically viable institutions that take your thoughts for granted. For example, Warren Buffett has acquired intellectual authority over financial markets because of the success of his company, Berkshire Hathaway, which was built around his idiosyncratic approach to investing. Steve Jobs acquired intellectual authority over design and computing because of the success of Apple, which was built around his personal taste. Books and companies aren’t the only two routes.

Even if an idea is communicated by someone with the relevant intellectual authority, this does not necessarily mean that it will be well-received or accepted as legitimate automatically. On a smaller scale, communicating the same idea can be received differently depending on the idea’s packaging.

Read the next essay in this series on intellectual legitimacy here.