Knowledge Production and Intellectual Legitimacy

This is the fourth essay in my series on intellectual legitimacy. Read the first essay here. Read the previous essay here.

We mostly evaluate knowledge by checking whether society at large perceives it as respectable and reasonable – we call this its intellectual legitimacy. This reliance is a consequence of our deep epistemic dependence on society. Legitimacy unfortunately is imperfectly coupled—and these days, quite weakly coupled—with the truth of a theory or its intellectual merit as a hypothesis.

We outsource most of this verification work to various institutions and respected individuals on the basis of their intellectual authority. However, we also always do some evaluation ourselves, as well. Depending on our competence or thoroughness, this gives truth an advantage.

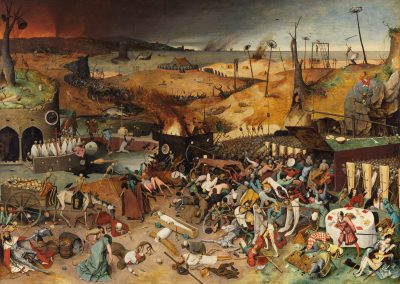

The advantage isn’t sufficient to imply that accurate or more advanced knowledge wins out in the long run. Especially in periods of intellectual decline, the work most likely to be transmitted and evaluated as legitimate is the work that is still understood. This means intellectual traditions of knowledge first die and eventually become completely lost. As a consequence, we have Pliny’s Natural History, a work of Roman popular science, but not the more technical Greek works it was based on.

Wouldn’t you notice if you were living through such an intellectual dark age? Most likely no. The authorities and institutions you would rely on would themselves suffer from the above problem. Reliably replacing all of these dependencies as an individual thinker is a task only achieved by the brightest minds in human history. The institutional impact of such a mind, if they can communicate with their society, can be immense, meaning they are often great founders.

Intellectual production isn’t always legible

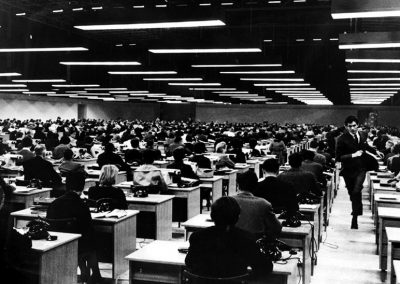

The most intellectually productive processes do not, by default, produce intellectual legitimacy. At one extreme, the most productive intellectual processes are also the most opaque: a form of intellectual dark matter. Consider, for example, a conversation between two experts over coffee. This conversation is dynamic and personal. The speakers follow the flow of thought together, relying on shared context and concepts. Although their conversation may be incredibly intellectually productive, where and how this knowledge is produced is very difficult to capture and communicate later.

A good example to illustrate the importance of intellectual production is Paul Erdős. Perhaps the most prolific mathematician in history, he published more than 1500 articles, mostly with coauthors. Erdős lived a vagabond’s lifestyle, wandering from the house of one collaborator to another and appearing suddenly at university math departments, furiously attacking problems from whatever field his interlocutor happened to be working on. This practice carried him into a vast array of different mathematical subfields. It seems unlikely that he originated all the key expertise attributed to him – more likely, he leaned on the experts he visited, making use of their knowledge and recognizing when it was novel or relevant. In other words, Paul Erdős’ key advantage was likely capturing the outputs of dynamic conversations and rendering them legible. We shouldn’t see this as diminishing his contribution – rather, the sheer effectiveness of such a strategy shows how neglected and vital such work is!

At the other extreme of intellectual legitimacy are the most legible and processed forms of knowledge. An example is the government memo, citing well-backed scientific studies and the decisions of many important individuals, each holding a responsible stake in society, widely publicized and available to the public for inspection. The problem with only recognizing or working on this kind of highly processed knowledge is that even in the most functional institution, a completely new field cannot emerge institutionalized. Intellectual golden ages occur when new intellectual authority is achievable for those at the frontiers of knowledge. Because of the abundance of opportunities for institution-building, intellectual golden ages are more common in rising rather than declining empires.

Building legitimacy at the frontiers of knowledge

As a consequence, someone pursuing the frontiers of knowledge must face the challenge of legitimizing their intellectually productive activities early in their career, assuming they are intellectually productive at all. This means finding socially legible justifications to engage in intellectually productive work, even if it isn’t considered legitimate. The work seen as a legitimate method of knowledge production will, after all, either be best suited to already-solved problems if institutions are functional, or even be completely useless if the institutions are dysfunctional and pursuing the appearance of knowledge, such as modern grad schools.

Anyone pursuing a frontier of knowledge sooner or later has to answer the question “So what do you do?” in a way that would be understood by a friend, sibling, or, perhaps, mother-in-law. I have known many promising thinkers who had a hard time explaining their early-stage projects to their parents, or to their childhood friends, or to potential dates. The psychological pressure is immense, and I often saw it drive people to abandon fruitful lines of inquiry. Every new successful field must establish itself as a known social category in the eyes of society. For a field to become prestigious, it must first be socially understandable.

This feat of social engineering is upstream of material or economic incentives, which is why an independently wealthy person cannot just throw money at any new field and expect it to stick. An economic justification is partially a social justification in and of itself, insofar as earning a living is considered necessary. This is usually insufficient on its own, and so the socially legible justification long precedes the economic justification. Even if an independently wealthy person threw money at a field, they would still have to be able to explain why they are doing so. Of course, once established, a field must also pay its practitioners competitively if it is to continue to exist.

Classical Greece offers a possible example of what a great intellectual impairment the lack of legitimacy can be even for fields possessing sound methods. Some historians have argued that their development of technology was held back by the negative connotations of manual labor as something befitting slaves rather than leisured philosophers. Such social pressure, then, interferes with applying observations about nature to engineering and experiments, even for independently wealthy aristocrats. Such prejudices, if they played a role in holding back Greek technology, were ultimately overcome in the later Hellenistic era where scientists such as Archimedes engaged in both mathematics as well as tinkering.

The first challenge of an intellectual career is the challenge of intellectual production, usually technically and intellectually tricky. The second is the challenge of legitimizing intellectual production so you are able to sustain this pursuit. The third is to find ways to produce a pipeline for the output of that work to become ever more legitimized, ever more official. If you fail in this third challenge, then other intellectuals will be interested in your output, but your work will not impact society and will be forgotten when your friends die. If you only follow the third step, you are a mere popularizer of others’ science. Only those who do all three can properly claim to be public intellectuals, a description deserved by only a few of those who are described as such.

Institutions inevitably claim intellectual authority

Given some of the serious challenges described, it might be tempting to try and find refuge in solutions that don’t require knowledge to be institutionalized. This first runs into the problem of how to solve the knowledge succession problem that is needed to keep traditions of knowledge alive.

Various proposals have been made for substitutes to legitimizing institutions, from universal literacy and education to technology-assisted wikis. All such solutions, when closely examined, reveal institutionalization hidden behind a curtain. The reliability of contemporary Wikipedia rests on a tight social network of obscure and enigmatic editors, rather than occasional contributions or vigilante edits from visitors. And universal literacy and education have never been achieved without the help of either states or organized religion, who always take the opportunity of educating the masses to put the stamp of legitimacy on their own ideas.

The second problem is that intellectual authority is too useful to power centers to be ignored. It will be deployed, one way or another. Social engineers have used it to guide behaviour, loyalties, and flows of resources for all of recorded history, and likely long before as well.

The most impressive example is the Catholic Church, which built its authority on interpretation of religious matters – which included human psychology, law, and metaphysics. The state Church of the Roman Empire outlived the Empire by many centuries. By the 11th century, Church authority was sufficient to organize and pursue political aims at the highest level. It was sufficient to force the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV to kneel for three days as a blizzard raged, waiting for the Pope’s forgiveness. Few military and political victories are as clear. The Pope was revealed as more powerful than kings. The power of the Pope didn’t rest primarily in his wealth, armies, or charisma. Rather it rested in a claim of final authority in matters of theology, a field considered as prestigious then as cosmology is today. This can be compared to the transnational influence of contemporary academia on policy and credibility.

Such exercises of power weren’t completely unopposed. Today it is often forgotten that Martin Luther’s 95 theses and debates such as that at the council of Worms were first a challenge of intellectual authority, and only consequently a political struggle. The centuries-long consequences of the Protestant Reformation are myriad, but one of them is the negative connotation of the word “authority” in the English-speaking West. Protestant pamphlets had harsh and at times vulgar critiques of Papal “authority”.

Merely making a word carry a negative connotation didn’t stop Protestant nations such as England or Sweden from creating their own state churches with much the same structure as the Catholic Church. Their new institutional authority was then a transformation of the old, using much the same social technology, rather than a revolution.

Inheritance of such authority shows some surprising patterns. The Anglican Church would famously have its own dissenters that ended up settling in the North American colonies. America’s Ivy League universities run on a bequeathment of intellectual authority which they first acquired as divinity schools serving different denominations of the many experiments in theocracy that made up the initial English colonies in the region. Harvard’s founding curriculum conformed to the tenets of puritanism and used the University of Cambridge as its model. Amusingly, the enterprising Massachusetts colonists decided to rename the colony of Newtowne to Cambridge a mere two years after Harvard’s founding. Few attempts to bootstrap intellectual authority by associating with a good name are quite as brazen!

Many know that UPenn served the Quakers of Pennsylvania, since the colony and consequently the university was named after its founder Wiliam Penn. But fewer know Yale was founded as a school for Congregationalist ministers, and that Princeton was founded because of Yale professors and students who disagreed with prevalent Congregationalist views.

The intellectual authority of modern academia was continuous from an era when theology could be the basis of intellectual authority, to a much changed contemporary society when the Ivy League reserve of intellectual authority was justified on new foundations. This shows that intellectual authority can be inherited by institutions even as they change the intellectual justification of that authority.

That such jumps are possible allows for interesting use of social technology, such as the King of Sweden bestowing credibility on physicists through the Nobel Prize or Elon Musk ensuring that non-technical engineers at his companies listen to engineers through designing the right kind of performance art.

Aligning intellectuals, institutions, and civilizations

These questions of intellectual attribution, authority, and legitimacy are interesting enough on their own, and are important to consider for anyone whose personal goals or strategy to achieve their goals requires intellectual work. If you want to become a world-renowned scientist, it’s good to understand how Albert Einstein became a world-renowned scientist. But these questions are far more important for societies and civilizations than they are for any single individual.

I have previously argued that the key driving force in the decline and collapse of civilizations is a breakdown in the social technologies that allowed them to prosper in the first place. Societies and—with an even greater bird’s eye view—civilizations are best understood as ecosystems of mutually interdependent institutions. In order to fulfill their intended purposes, these institutions require careful stewardship and maintenance by live players with both the skill and the authority to command, modify, or even dismantle them. These live players need to both understand and be able to alter the social technology governing the load-bearing institutions of a society or civilization.

To achieve this, they must ultimately have the knowledge of how the relevant institutions actually function, or they must be trained in a tradition of knowledge that allows them to figure it out on their own. In either case, a society’s institutions will have far more capable leaders if it also has institutions devoted to the production and transmission of knowledge key to its own functioning. The default state of affairs is that this knowledge, whether suddenly or gradually, fails to be transmitted from one generation of institutional leaders to the next. It becomes intellectual dark matter.

If intellectual legitimacy is not granted to ideas key to a society’s functioning or renewal, then those ideas cannot be used to reform non-functional institutions and the institutions will eventually fail. If intellectual authority is not aligned with actual expertise on a subject matter, a society’s institutions are almost guaranteed to be systematically misled on any number of practical matters. Truly new intellectual production may not be strictly necessary for a society to avoid decline and collapse, but it often helps, and it helps most when maintaining, transmitting, and producing useful knowledge leads to the legitimacy and authority required to implement it in practice.

Aligning all of these components so that there is a straight line of benefit from intellectual work to the functioning of a society is itself a task for great founders. Important knowledge must be institutionalized not only to make sure that intellectuals can pay their rent, but to ensure the perpetuation of society itself.

Read the previous essay in this series on intellectual legitimacy here. The first essay is available here.