How Roman Emperors Handled The Succession Problem

This is an excerpt from the draft of my upcoming book on great founder theory. Learn more here.

Institutions built by one generation of founders must be successfully handed off to the next to keep them functional. In the absence of such succession, organizational sclerosis or constant internal conflict sets in.

The succession problem has two components: skill succession and power succession. In public discourse and political thought we have tried to solve either power succession or skill succession under different names. We seamlessly switch between two separate fragmented states of mind depending on which component of the problem is in front of us without even noticing.

Our culture is pervaded by an ideology of proving worth through struggle. This almost Darwinian view is strongly present in our economic, political, and even academic values. We define merit by equating it with success in competition, not even realizing this was merely one of many possible choices.

These values then underwrite various legal and social obstacles imposed on power succession, that are widely believed to solve skill succession: we believe that by disempowering the holders of institutional positions from choosing their successors, we ensure that they will be replaced based on “merit.” When it comes to our private decisions, though, we have a more nepotistic mindset. In the private realm, we can think more cleanly about power succession. In this mode we usually fudge skill evaluation, however.

We assume that power and skill are unrelated at best and, often, further assume that power is ill-gotten by those who seize it without any warranted skill. What is missing from Western understanding is that power succession and skill succession are not actually at odds with each other, but are actually two mutually necessary halves. If your goal is to keep institutions functional, solutions that solve one but not the other are not solutions at all.

To explore and illustrate this reality, we can look to the example of adult adoption in the Roman Empire, which will provide insight into what kind of social norms and institutional features would be necessary in a modern solution.

When in Rome…

Roman society is correctly noted for its production of highly skilled individuals. It had no problem with skill succession — ambitious and greatly talented individuals abounded. They did find power succession to be a challenge, however, especially in the later eras of Roman civilization, when the cooperative elites of the early Republic were no longer around.

It’s worth emphasizing just how anomalous the early Roman Republic was. For example, Cincinnatus could be called upon by the Senate to be dictator in an emergency, then earn the admiration of his peers by choosing to seamlessly retire back to his farm after the crisis passed, without fear of reprisal from former political rivals. They trusted that his retirement was genuine and that he would no longer be a towering figure in politics.

Contrast this with modern Libya, an example at the opposite extreme. Muammar Gaddafi’s gruesome death at the hands of the National Transition Council militia is infamous. Even absent the American and French interventions that toppled him, if he had handed power over to his political opposition, a peaceful retirement seems unlikely at best.

The Roman republican system eventually met its limits as it grew from managing a provincial Rome and its client states on the Italian Peninsula to managing a more complex urban economy and the political life of the entire Western Mediterranean. Problems that previously could have been solved by aligned political fundamentals or the social fabric of the patrician class grew difficult. They fell more and more on the formal religious and legal structures of the republic.

These structures, once the last recourse, could not bear the burden of regular use. What were once dire contingencies only to be resorted to in the case of a failure of coordination among the governing class, came to be seen as normal political moves. Roman economic, military, and political elites grew steadily less cooperative as a result.

By the late republic, talented people still arose but were forced to fight bloody civil wars to resolve disputes. The career of Sulla, for example, is littered with political opponents defeated not just on the senate floor but on the field of battle. An informal no-rules political sphere superseded the formal one, with dangerous consequences.

Long after these civil wars changed the Roman state beyond recognition, Roman Emperors found an inventive solution for the newly apparent problem of power succession. In subsequent periods of stability, such as during the Nerva-Antonine dynasty, this was achieved with the use of adult adoption.

In Roman society, adoption wasn’t solely a means to help orphaned or abandoned children, but a social and legal mechanism through which you could make an adult male your son and heir, allowing him to inherit your position. In other words, your dynasty didn’t need to end with your bloodline.

This solution had many interesting features, the most notable of which is that the emperor could work out an agreement with a rising younger rival, bringing him into the fold and aligning his aims with the emperor’s. Adoption legibly positioned them as the natural successor.

Since the practice of adult adoption was well understood and respected throughout Roman society, it amounted to a credible guarantee of coordination. Credible guarantees changed incentives notably.

The adopted son, who might previously have been tempted to undermine the emperor, would now be in favor of expanding a power base that would one day be his. The current and future rulers, then, have a reason to work together even before the transfer of power is affected. The result is not only a peaceful transfer of power, but a political alchemy that transmutes your most dangerous rival into your most potent ally.

A well-respected law backed by legal practice is what ensures that wealth and other legal rights are properly transferred. Importantly, the legitimacy of the social practice of adoption, together with the mutual expectation of future power, meant that intangible social connections, so vital to securing power, are transferred as well.

Even if the chosen successor and head of state were not in the closest political allegiance due to other factors, this adoption mechanism could still be used to formalize the capacity to carry out a coup to put that person in charge, or at least in the waiting line for formal governance, without a civil war. This solved one of the greatest difficulties with negotiated surrenders and peace negotiations in general: that of credible commitment.

The mechanism had benefits in terms of skill succession as well, since it allowed a skilled pilot, in this case a skilled ruler, to recognize and pick another with comparable skill. As a result, the era of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty saw relatively peaceful and competent governance.

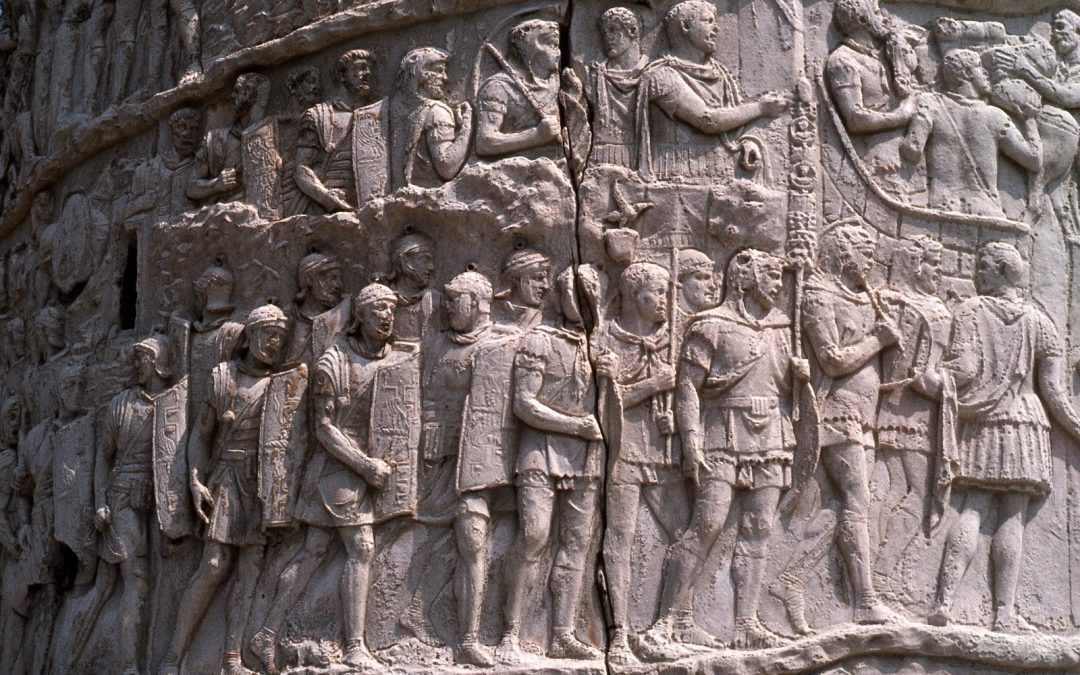

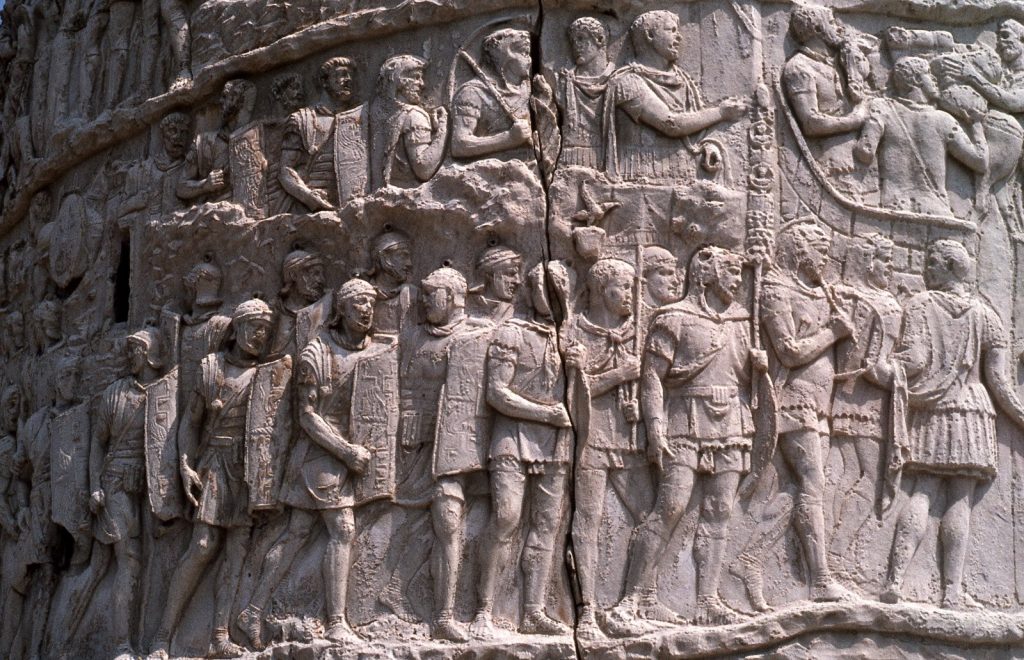

The term “Five Good Emperors” has been used to refer to the chain of five good rulers from the Nerva-Antonine dynasty (Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius). The famous British historian Edward Gibbon went so far in his praise as to say mankind never had as happy a condition before or after as under their rule.

The relative harmony of this period provides an important contrast with the civil wars seen earlier in the late republic and later in imperial history. Adoption proved a viable method of solving power succession, allowing the emperors to enjoy personal security that curtailed the problem of local focus, which in turn ensured effective control and good functioning of the expansive Roman state.

During his brief reign, the politically weak emperor Nerva chose to adopt the up and coming Trajan, formalizing his rise and integrating him into the governing structure without a bloody civil war. Trajan’s successor, Hadrian, was also adopted, though details are murky, as the documents were signed on Trajan’s deathbed. What is clear, though, is that Hadrian was a long-standing member of Trajan’s inner circle—according to the Augustan History, it was Hadrian who brought the news to Trajan of his adoption by Nerva—and seems to have successfully learned the skills of governance outside of his posts in formal positions of power. Hadrian in turn adopted Antoninus Pius, who had greatly impressed him with his performance as proconsul of Asia, under the condition that Antoninus himself adopt both Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus as heirs. He did so, and upon his death was succeeded by both Marcus and Lucius, who co-ruled until Lucius’s death. Marcus Aurelius would, of course, name his erratic biological son Commodus as heir, a decision subject to great debate but which seems to have resulted in a failure of skill succession.

The more complex the solution, the more fragile it is

The most developed version of the system of adoptive succession was implemented centuries later under Diocletian, the reformist ruler who brought the empire back from the brink of collapse. The practice of adoption was less prominent in Roman society by that point, so the stability of the guarantee was more questionable, since it was no longer a celebrated cultural practice. Diocletian revived it for use as a legal succession mechanism and developed it further by implementing a system of seniority and apprenticeship. The appointed successor was granted the title of Caesar (junior Emperor) and would be allowed to manage their own lands, under nominal supervision of the Augustus (senior Emperor).

This sweetened the deal: not only will I name you my son and, by culture and law, make you my heir, but I will also grant or acknowledge your right to manage territories right now.

An advantage of this approach is that the senior position is directly analogous in terms of the skills and responsibilities required of the junior one. The job of head of state is usually sufficiently unique that preparation, training, and directly relevant experience are infamously hard to come by. A disadvantage of this approach, however, is that it favors the junior party, perhaps to the point of making premature conflict a viable route to power.

The Roman Empire was experiencing great difficulties in this era, having become sclerotic and bureaucratized. Military and administrative demands made the division of the Empire into a Western and Eastern half politically advantageous. In the landscape of power, high was then composed of a four-way alliance, a tetrarchy of the Eastern and Western senior emperors, and their junior successors.

This complicated arrangement proved more unstable than the Nerva-Antonine dynasty. The balance of power between four skilled individuals is a hard thing to maintain. Every now and then there do arise cooperative strategists that can make such a balance of power work, but the skill requirement for the job is significantly higher than the earlier Roman arrangement. The tetrarchy was stable only under the management of Diocletian himself. He managed the feat of safely retiring, but unfortunately in his old age he also lived to see the system fall.

More complicated systems of succession and coordination are generally fragile, since in those cases successful power succession relies on successful skill succession, as navigating the process of succession becomes a skill unto itself that must be transferred between generations. The more robust approach is to aim for skill succession, but enable power succession in its absence or partial success.

There are examples of seemingly very complex systems of succession that have endured for centuries. An example of complicated constitutional arrangements was the Republic of Venice, the longest-lived republic in history. Such arrangements are however best thought of as very complicated legal machinery that validate and render legal any decision arrived through some other means; the selection of the Doge of Venice was likely accomplished by direct negotiation between the patrician families of Venice, not through the nominal selection procedure.

Lessons for contemporary society

Successfully transferring not only the formal, but also informal, position that allows an individual to shape an organization is necessary for keeping an institution functional. On the scale of societies, employing solutions that prevent destructive conflicts between elites is vital.

The adoption of adults was a viable solution in the Roman Empire for as long as the social fabric underwriting it was there. As the underlying social norms changed, the legal norms that made it possible required backing by more and more complicated mechanisms and workarounds. This architecture proved less successful, in part because its complexity made it more difficult to maintain.

We cannot simply copy the Roman solution, because our own social and legal norms are different. While adult adoption is legal in many Western countries, the Roman social practice would be considered an exploit, and would leave companies and organizations that used it open to legal or PR attacks. The challenge, then, is finding a solution that would work as well and is as simple as possible.

It is important to note that, in modern Japan, a technologically developed industrial economy, we actually observe a similar practice. A son-in-law is chosen by a businessman primarily for his ability to run the family business, and called a mukoyōshi. They marry into the family and take on the family name. The practice can be found in the history of companies such as Suzuki, Kikkoman, and Toyota.

It might be tempting to try to imitate mukoyōshi in the Western context. The legal vehicle of marriage certainly seems more appropriate for the task than our adoption laws. The crucial problem, however, lies in how we choose marriage partners in the West. Our choice of spouse is a personal and romantic, rather than a business and family matter (though of course some minority of us do set out to “marry up”). This means that while we could use marriage for power succession, its appropriateness for solving the problem of skill succession is dubious.

Despite the obstacles to its direct application, the Roman solution displays features we can and should emulate in our own institutional thinking. When pursuing reform, setting cultural expectations, or building new organizations with the intent to solve the succession problem, we should aim for simplicity and robustness of mechanism , have the mechanism transfer informal as well as formal resources, and ensure that the incentives of the successor and the current pilot are as aligned as possible.