Live versus Dead Players

This is an excerpt from the draft of my upcoming book on great founder theory. Learn more here.

Whether you are examining past societies or living and acting within one today, it’s important to distinguish between live and dead players. A live player is a person or well-coordinated group of people that is able to do things they have not done before. A dead player is a person or group of people that is working off a script, incapable of doing new things.

This distinction matters both for pragmatic and strategic reasons: it tells you how to act both offensively and defensively. Offensively, if you figure out whether a player is alive or dead, you can predict how they will respond to things and what that means you can do. If you find out that a player is dead, then you know that you can confront them in ways that are not known to them, and they will not be able to fight back. On the other hand, if you fail to figure out that a player has died, you might not realize that you can get away with replacing them. Defensively, paying attention to live players allows you to anticipate and prevent the grabbing of power, for instance.

The distinction between live and dead players also matters if you are trying to predict the future of society. You can predict what will happen in a society if you understand its landscape of live players. Societies with few live players will stagnate; societies with many live players will develop and adapt.

Whether a player is alive or dead is always relative to themselves. Thus, a live player is not necessarily exceptional in skill, although this is usually the case. If a player has already done X, doing X again does not make them a live player, even if other players can’t do X yet or X is an impressive move. The player would have to make a move that is new for them in order to be a live player.

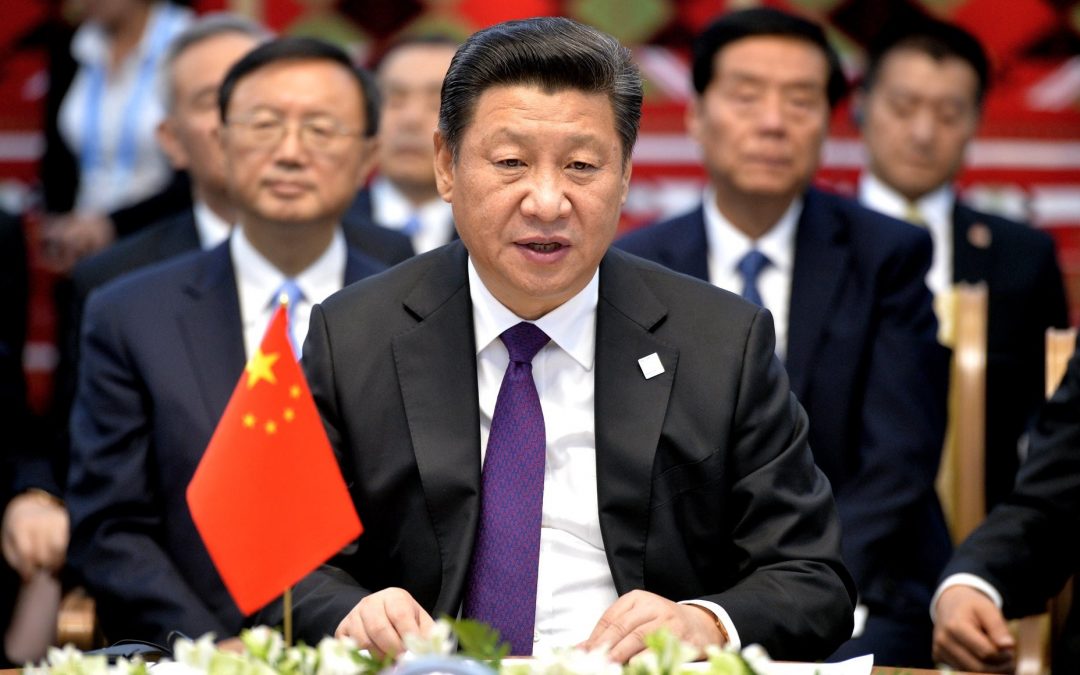

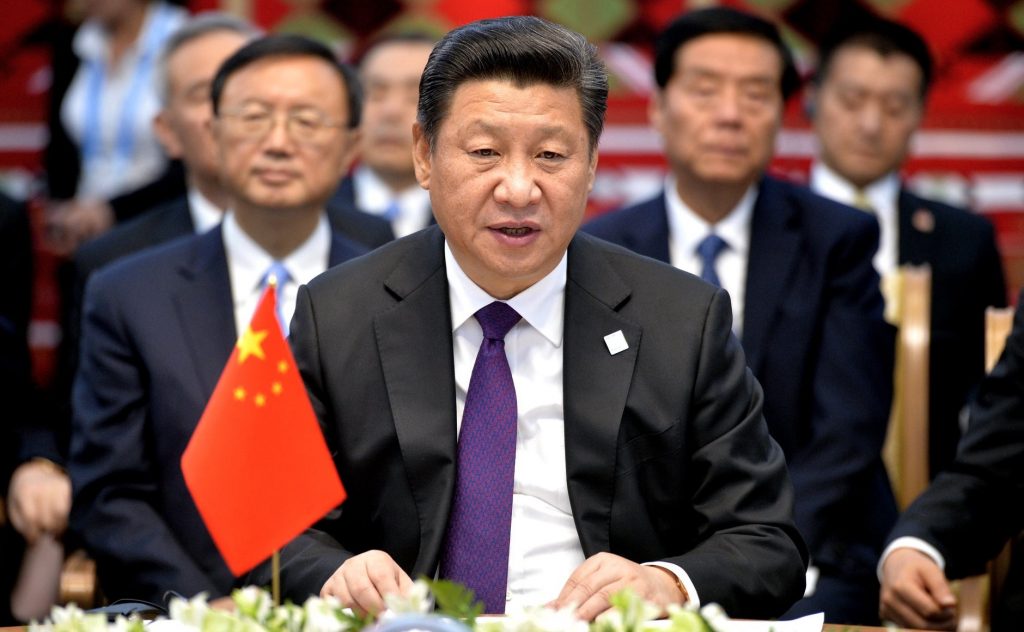

For example, Vladimir Putin is a live player, and by virtue of his piloting the institutional machinery of the Russian state, Russia is also a live player. The Russian state is doing things it hasn’t done in a long time, things that were unthinkable a few years ago. Russia annexed Crimea, for example, and such a thing hasn’t been done in Europe for decades. It also completed a successful military operation in Syria, notable in part because Syria is beyond Russia’s geopolitical stronghold of peripheral former Soviet states in its “near abroad,” and Putin managed to achieve his foreign policy objective of stabilizing Assad at considerably less cost than comparable American interventions in the Middle East.

Russia didn’t have much time to develop plans for Syria—perhaps three years—which means it had to pull things together quickly. This is a very strong indicator that Russia can figure out new things, and quickly too. However, one country having this kind of influence over another country is nothing new—it’s merely new for post-Soviet Russia, which is why we would deem Russia a live player. This same action taken by France in Mali would not indicate that France is a live player, for example, because France has routinely intervened in West Africa. A bureaucratized action, even if it is an impressive action, is not a sign that the player is alive.

It is possible then to describe the characteristics of live versus dead players in greater detail, which will help in distinguishing between them.

Live Players

It’s worth restating the definition of a live player: a live player is a person or tightly coordinated group of people that is able to do things they have not done before. There are two attributes that are necessary for a player to be considered live: tight coordination and a living tradition of knowledge.

If not merely one individual, a live player that is a group of people must be tightly coordinated in order to be flexible and responsive enough to do things they have not done before. This allows them to make moves outside of the formal structure of the group, go off script, modify themselves, continue acting even if the outer form dies, and so forth. Imagine, for example, an engineering team that keeps working together successfully after the company they work for formally blows up, perhaps transitioning together to a new company or just coordinating as hobbyists on the side.

The generation of new tactics, strategies, coordination mechanisms, and so on entails the production of new, useful knowledge. Thus, a live player must have a living tradition of knowledge. For the tradition of knowledge to be living, it must have at least one theorist, among other things. An individual live player may fulfill multiple roles in themselves, including being one’s own theorist.

Signs of Live Players

What are signs that a player is alive? One strong sign is a player doing things outside of their expected domain—in a new, unexpected domain—which indicates that they can figure out new things for themselves.

Take Steve Jobs. Not too long ago, we saw Apple fighting against compliance with government requests for backdoor access to its data. This means that Jobs had previously found a way around compliance, which also means that Jobs was able to figure out ways to deal with the intelligence world. This was outside of his expected domain of building technology companies. This is a strong sign that Apple, at least while piloted by Steve Jobs, was a live player.

Another sign of a live player is exceptional individuals gravitating towards them. Such individuals tend to be good at assessing others, and will tend to seek out others who are also exceptional. If they cluster around a person or group, there is something exceptional about that person or group. Successfully reverse-engineering an attack is another, albeit weak, sign of a live player. Those who can make novel moves will also tend to be able to reverse-engineer moves, but those who can reverse-engineer moves often lack the ability to create novel ones.

Spotting live players is made difficult by the live players themselves. Live players frequently conceal themselves to avoid opposition from other live players or to reduce the likelihood of attacks. By concealing themselves, they delay other people’s responses to them. For example, Amazon branded itself as a book-selling company long after it stopped being merely a book-selling company. This helped it avoid having Walmart think of it as a competitor. Nowadays, Amazon might prefer people think of it as a competitor to Walmart, to avoid people thinking of it as a competitor to SpaceX, Microsoft, or even the U.S. government.

Dead Players

We defined a dead player as a person or a group of people that is working off a script, incapable of doing new things.

What can cause a player to die? A player will die if their tradition of knowledge dies and they are unable to replace their thinkers or theorists. Perhaps an individual live player simply runs out of ideas. Even if tight coordination remains, the player is dead. They will compete in old areas, but have a hard time expanding into new areas.

A player will also die if their tight coordination is replaced by formal structures, which can happen as members of an organization change. If you’re constrained by formal structures, it becomes harder to go off script, and this won’t be adaptive enough. Remember, however, that tight coordination can be achieved by just one exceptional person.

Revival

How can you revive a dead player? It only takes one great person to revive a dead player. That said, reviving a dead player is challenging—more challenging than reviving a dead tradition of knowledge. In order to revive a dead player, you have to displace an existing power structure. It is frequently easier to do this by conquering the existing power structure with outside, owned power, than by trying to transform the player from dead to alive from the inside. This is because a dead player, if it is an organization, may contain mechanisms that preclude insiders from gaining enough power to restructure it into a live player.

Apple is an example of a dead player. It became much less interesting and powerful after Steve Jobs’ death. Under him, it was a cultural and commercial force that was able to interface effectively with the U.S. government. Now, it is a bureaucracy imitating his taste. It is incapable of adapting, building beautiful new things, and acquiring power.

It’s much easier to detect live players than it is to detect dead players. This is because seemingly dead players might actually be alive (and playing dead).